Lest we forget

MS W.82 Prisoner of War in Siam, by Ralph Edward Ince (1905-1996)

Next month marks the seventieth anniversary of the uniting of the two portions of the ill-famed Burma-Siam Railway, on 17 October 1943.

Amongst Johnian war memoirs the Library has, by kind gift of Mr and Mrs D. McCarthy, a typescript copy of recollections of Ralph Ince (matric. 1924), who was a teacher and education officer in Singapore and at the outbreak of war joined the Johore Volunteer Engineers as a sapper. Taken prisoner at the city’s fall on 15 February 1942 and liberated in August 1945, Ince was one of the multitude of Allied PoWs and impressed local labourers who built the line, and one of far fewer who survived to write of it.

While we now take for granted the ready abundance of war memoirs by officer and other ranks alike, Ince was prompted to write partly in order to give an account of ‘the experiences of one in the lowest grade of Military life - one who was not only at the mercy of the Japanese but of every whim of the Military Hierarchy of our own Army’, a perspective which, when writing in 1948, he found absent from the public arena.

Ince set out ‘not [...] to catalogue horrors but rather to relate the more interesting happenings,’ which he does in a remarkably generous and mild tone. He revels in the smallest drop of sweet in the sea of bitter circumstance.

Having endured months of peril and cruelty during completion of the rail line, he observed one day ‘a big tough looking Japanese N.C.O.’ work carefully around a wretchedly ill PoW so that bamboo sawn off a hut should not fall and hit him - behaviour utterly unexpected, and credited as ‘one of those queer incidents which made one realise that some Japanese had kind hearts’.

Even a bad case of trench-foot is appreciated for the luxury it afforded: ‘It is hard to describe how pleasant it was to be officially sick for a few days and actually to wake in the mornings knowing that one had absolutely nothing to do all day except talk, eat, doze and occasionally go to the M.I. “Room” for dressings.’

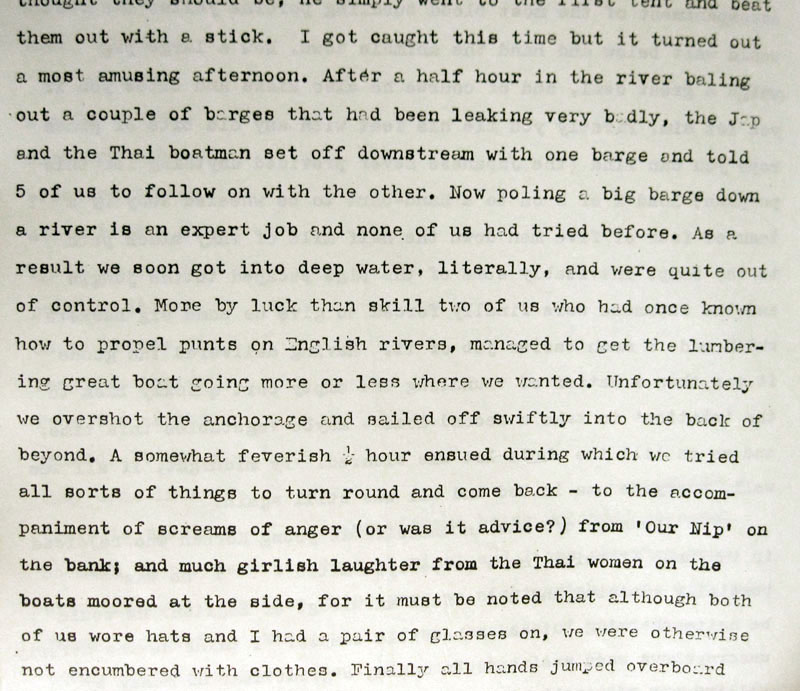

There is also a good dose of humour in his account. In this passage, he tells how, having worked in the previous night and through the morning, he was roused from a brief, exhausted sleep to more labour, and the exercise of a surprisingly transferable Cambridge skill - though with slightly different sartorial arrangements:

Unsurprisingly, food features prominently—its lack, its supply, its variety. At one point they lived almost entirely on pork, occasioning a bout of jaundice which was gradually dispersed ‘on a diet of rice and strawberry jam (which I was fortunately able to buy with a little accumulated savings)’.

To all of us the only ray of hope of ever getting out of this awful place was that the railway might one day be completed, and our work done.

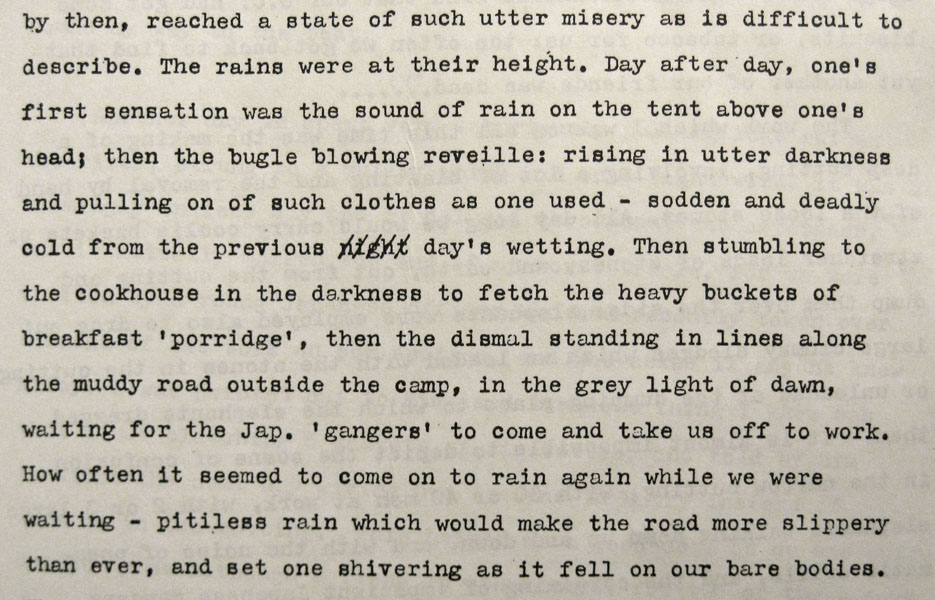

Sent up to the ‘hell spot’ of the camp beyond Tarkanun [Tha Kha-Nun] known only as ‘211’ - ‘I suppose it was eloquent of our camp at the 211 K.M. that nobody ever gave it a name’ - Ince records the time known as the ‘Speedo’, the ruthless drive to finish the railway in the worst months of the Monsoon:

After the dash along the road and up the slick, steep slopes on all fours (‘all this as fast as possible for the earlier one got to the site, the better the chance of avoiding the worst of the jobs’) came the long day’s toil, clearing by hand earth and stone from a deep cutting being blasted in the jungle:

It is almost impossible to depict the scene of confusion in the narrow cutting, with 30 or 40 men at work, with 2 or 3 large elephants walking up and down, and with the noise of pneumatic drills, and the screaming of impatient Japanese gangers adding to the chaos. As might be expected the ‘floor’ of the cutting was mostly covered with water, so that we stumbled uncomfortably about with our heavy loads, slipping in and out of the pools and cutting what remained of our boots to pieces on the sharp rocks hidden below the mud.The unrelenting pace continued until

to my great astonishment, one day we realised that the Track laying party was working nearby. They laid over 2 kilometres of metals that day and on the morrow, trains were running past through country which a month previously had been a sickening nightmare of hills, ravines, and cruel forest. Altogether the work on this section had been completed in about four month - as near as I can recollect.

In those months, of the twelve with whom he formed a hand-cart team on the march up, ‘only seven lived to make the return journey’.

For some survivors the anniversary may chiefly be marked with a recollection of relief amongst the dark memories: the completion of the work on that stretch did mean the end of ‘211’ and, for Ince at least, the worst of his time in captivity. On return to the prison camp at Chungkai the contrast was so great that ‘For the time being one had the illusion of having, in fact, been liberated’.

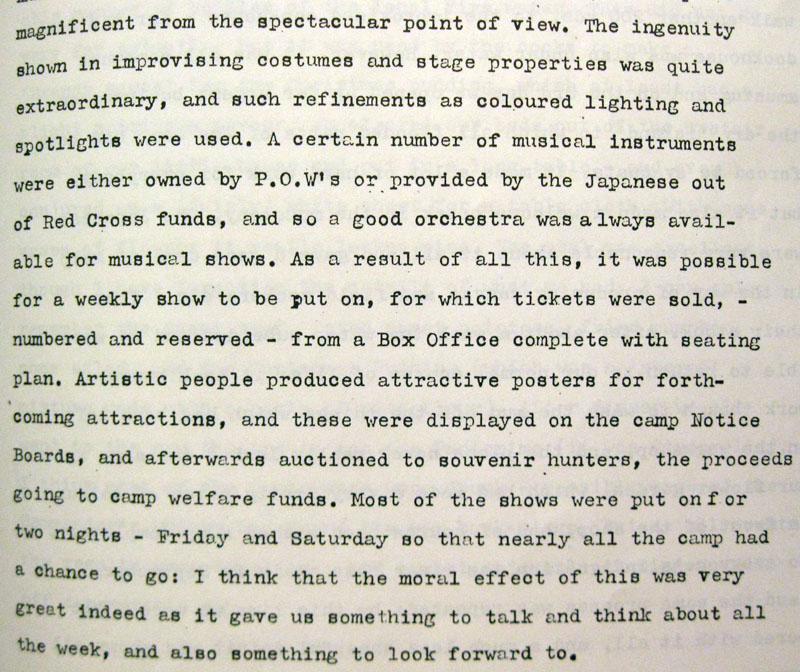

As well as the better living conditions and ‘more congenial work’, chiefly in the tinsmith’s shop, he writes enthusiastically about the bright spot in the lives of all those in the camp: the Chungkai Theatre. With the ‘remarkable amount of talent available’, including an ex Hollywood producer, the shows proved to be not only well acted but ‘quite magnificent from the spectacular point of view’.

Ince was transferred to the Bangkok (New Harbour) Camp on 1 August 1945, and by the end of the first week uncertain rumours and hints were swirling about that the war was over. When definite word finally came, ‘we were all struck at once with the enormity of the anti-climax of it all. [... T]he arrival of the end had come so gradually: had the announcement come as a complete surprise, we should no doubt have gone "off the deep-end" as they did in other camps.’

Celebrating the first official news of freedom took a thoroughly practical turn in the insect-infested camp: ‘On the first day, with one accord, we ripped out our floor boards and threw them out to burn in the roadway: the number of bugs that were slain that morning must have been legion.’

Ralph Ince returned to teaching in Singapore after the war ended, and served for a time also as Chief Commissioner of Scouts in Singapore and as an organist at Singapore Cathedral.

[N.B.: Every effort has been made to trace the successor copyright holder and to obtain permission for the use of copyright material, but without success. The Library would welcome any information that would permit us to redress this situation.]

This Special Collections Spotlight article was contributed on 12 September 2013 by M. Marvin, Manuscripts Cataloguer.