An incipient vacuum

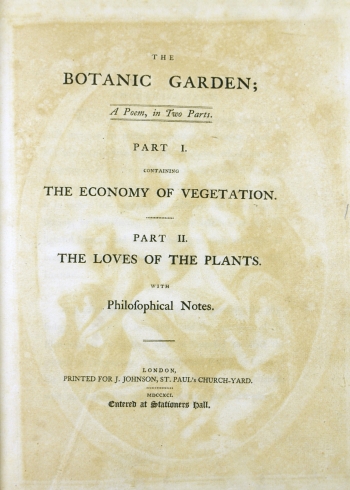

Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles, and a student at St John’s in the 1750s) published the collected version of his two-part poem The Botanic Garden in 1791. While the book - the first edition of which is pictured here - does have plenty to say about botany, it is more broadly concerned with celebrating and advocating for scientific discovery, with the poetry inherent in fact, and with considering humankind as an aspect of the natural world rather than somehow separate from it.

For an example of how these interests are harmonically expressed, one might look to an excerpt from the third canto of the poem’s first part, The Economy of Vegetation. A block of verse beginning with the exclamation ‘Nymphs!’ will not seem promising to those in favour of rigorous investigative procedure, but such rhetoric can be taken in one’s stride in the name of appreciating the connective leaps Darwin performs.

Nymphs! You first taught to pierce the secret caves

Nymphs! You first taught to pierce the secret caves

Of humid earth, and lift her ponderous waves;

Bade with quick stroke the sliding piston bear

The viewless columns of incumbent air;—

Press’d by the incumbent air the floods below,

Through opening valves in foaming torrents flow,

Foot after foot with lessen’d impulse move,

And rising seek the vacancy above.—

So when the Mother, bending o’er his charms,

Clasps her fair nurseling in delighted arms;

Throws the thin kerchief from her neck of snow,

And half unveils the pearly orbs below;

With sparkling eye the blameless Plunderer owns

Her soft embraces, and endearing tones,

Seeks the salubrious fount with opening lips,

Spreads his inquiring hands, and smiles, and sips.

In a footnote, Darwin makes clearer his observation that the process of drawing water from the ground is analogous to breastfeeding: the infant, the ‘blameless Plunderer’, ‘learns to make an incipient vacuum in its mouth, and acts by removing the pressure of the atmosphere from the nipple, like a pump’.

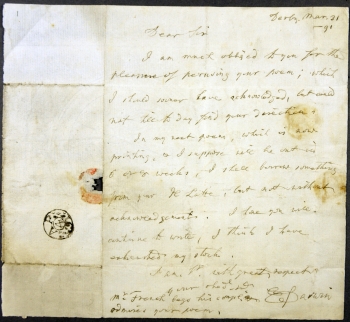

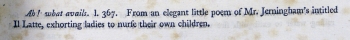

At this point, Darwin permits himself a digression, and having explained how breastfeeding happens insists that it should happen, and that, as he has already suggested, it should specifically be carried out where possible by ‘the Mother’. Before quoting more from the poem, it is worth noting that the stuff of Darwin’s argument is not original to him, being borrowed from Edward Jerningham’s poem ‘Il Latte’ (‘Milk’). Jerningham and Darwin had some correspondence, and the letter (31 March 1791) in which the latter expresses his intentions towards the former’s poem is held in the Old Library at St John’s.

The key portion of that letter reads:

In my next poem, which is now printing, and I suppose will be out in 6 or 8 weeks, I shall borrow something from your Il Latte, but not without acknowledgements. I hope you will continue to write. I think I have exhausted my stock.

The ‘something’ that caught Darwin’s eye in Jerningham’s poem (where the ‘blameless Plunderer’ is, charmingly, an ‘unblam’d inebriate’) is in these lines:

Ah! what avails the coral crown’d with gold?

Ah! what avails the coral crown’d with gold?

In heedless infancy the title vain?

The colours gay the purfled scarfs unfold?

The splendid nurs’ry, and th’ attendant train?

Far better hadst thou first beheld the light,

Beneath the rafter of some roof obscure;

There in a mother's eye to read delight,

And in her cradling arm repose secure.

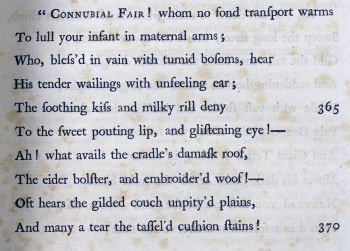

Aided by his adoption of couplets rather than alternate rhyme (and employing a less-is-more principle that most people favour with regard to poetry, often to an extreme), Darwin compresses the essence of Jerningham’s eight lines into six:

The eider bolster, and embroider’d woof!—

Oft hears the gilded couch unpity’d plains,

And many a tear the tassel’d cushion stains!

No voice so sweet attunes his cares to rest,

So soft no pillow, as his Mother's breast!

The specific images differ, but the position is the same: there is no point in surrounding your baby with aesthetic luxury, as all a baby wants is the less flamboyant, more practical comfort and nourishment its mother can provide. Making his case by way of artistic composition, Darwin is nonetheless speaking against human artifice and pretension insofar as they disconnect people from the best natural impulses. And one might, if so inclined, find here a still-pertinent critique of the prioritising of superficial public decorum over more fundamental humanity. ‘The Cherub, Innocence,’ he writes, returning to his mythological framing, ‘with smile divine | Shuts his white wings, and sleeps on Beauty’s shrine’: with no indulgence in notions of embarrassment or disgust, it is a more warmly, generously enlightened view of these matters than many in the 21st century have achieved.

This Special Collections Spotlight article was contributed on 15 April 2015 by Adam Crothers, Library Assistant.