Humphry Repton: Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening

Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803) was the second of a number of influential treatises on landscape gardening compiled by the self-proclaimed 'landscape gardener' Humphry Repton (1752-1819). This impressive 1805 edition was donated to the Library by the Johnian lecturer and former College Librarian, Hugh Gatty (1907-1948), whose large bequest is a rich and diverse selection of manuscript and printed material spanning many centuries, including several 19th century fine books on gardening.

From rather tumultuous beginnings as an unsuccessful textile trader, experimental farmer and uncredited ‘inventor’ of a reformed mail-coach system, Repton pursued his talent for drawing and writing, along with his interest in socialising with powerful members of landed society, and managed to succeed the famed ‘Capability’ Brown as the most significant landscape designer of his day. In contrast to Brown, Repton deftly exploited the printing industry, securing his professional reputation by promoting his work in various beautifully illustrated morocco-bound manuscript volumes:

'When called upon for my opinion concerning the improvement of a place, I have generally delivered it in writing, bound in a small book, containing maps and sketches, to explain the alterations proposed: this is called the Red Book of the place; and thus my opinions have been diffused over the kingdom in nearly two hundred such manuscript volumes' ('Advertisement', 6).

Towards the end of his life in 1816, Repton had increased this figure to more than four hundred red books and manuscript reports. On occasion, such volumes were comissioned with no intention of ever being implemented, but as attractive 'artist's books' for the libraries of various country houses.

Although it reproduces many lavishly coloured sketches taken from his red books, Observations is consciously a more practical affair. Influenced by his partnership with the architect John Nash from 1796, Repton used the book to explore relationships between landscape and architecture. As he writes in the ‘Advertisement’ preceding the work:

‘I have […] collected such observations as may best vindicate the Art of Landscape Gardening from the imputation of being founded on caprice and fashion […] I must therefore intreat that the plates be rather considered as necessary rather than ornamental', (5-6).

In reality, Repton trod a fine line between the ‘Art’ of landscape gardening (the ‘picturesque’ style championed by two of his adversaries, Richard Payne Knight and Uvedale Price) and the more hands-on approach of 'Capability' Brown. Although disparaging of ‘impracticable theories,’ unlike Brown, Repton was rarely involved in the workmanship of implementing his designs on the ground - his income, therefore, relied almost entirely on the design-stage of developments, which he exploited to great effect through the publications of his writings and sketches. Observations is a good example of Repton's efforts to expand the readership of his works by publishing printed volumes garnered from 'various manuscripts in the possession of the different noblemen and gentlemen for whose use they were originally written' ('Title page').

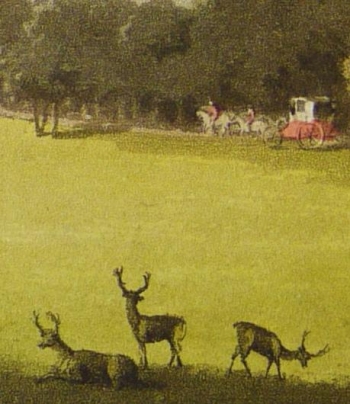

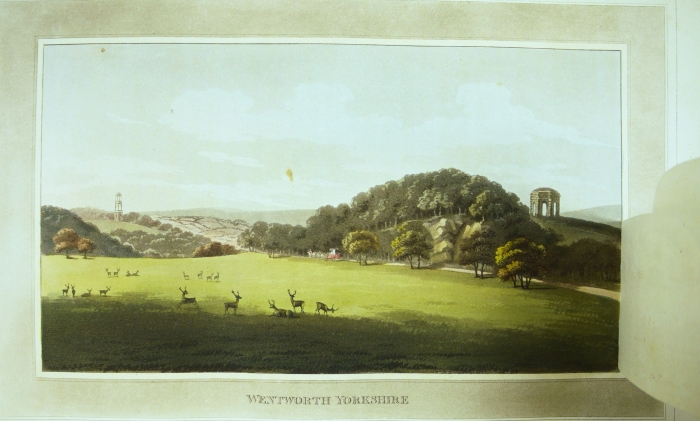

An especially enjoyable feature of the book is Repton's use of hinged slips attached to his coloured plates, which can be pulled away to reveal his proposed changes. The example below shows Wentworth Woodhouse, an 18th century country house in South Yorkshire, transformed from a modest area stunted by a shallow hill into a scenic vista that seems to extend far into the distance along the newly-planted line of trees. Repton's interest in the 'theatre' of design is evident here. He was fascinated by the optics and illusion of landscape design, both in manipulating perspective to recast the physical landscape and in the 'magical' performance of unveiling, central to his hinged illustrations.

Wentworth Woodhouse, Yorkshire: present and proposed scenes.

Wentworth Woodhouse, Yorkshire: present and proposed scenes.

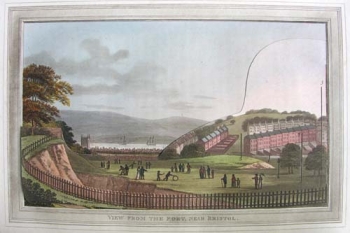

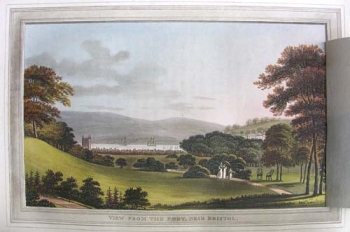

The Fort, Bristol: present and proposed scenes.

Particularly concerned with what he termed 'the late prodigious increase of buildings' which had 'so injured the prospect of the house', Repton set out to conceal any evidence of the burgeoning industrial port of Bristol in these plans detailing proposed changes to the Royal Fort House grounds (7). The 'unsightly rows of houses' miraculously disappear under cleverly planted trees and groups of the wrong sort of people are replaced by the serene wanderings of right kind (8). A favourite technique of Repton's was to 'borrow' objects from the surrounding landscape (in this case the church tower on the left-hand side) and seemingly embed them within the bounds of the grounds. By feigning a naturalised context, Repton had great success in producing a strikingly 'untouched' harmonious effect without making dramatic structural changes. As he wrote: ‘the great materials of the scene are provided by nature […] the artist must satisfy himself with the degree of expression that she has bestowed’, (108).

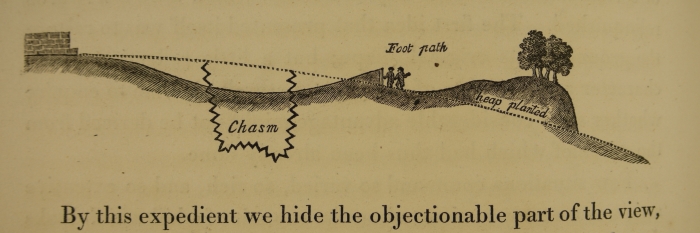

A key 'problem' with the site as far as Repton was concerned was a public right of way running along the base of the park. The diagram below shows Repton's solution to this 'objectionable' situation, by creating a bank to hide any passing locals, as well as concealing the house from their view.

Concealing the 'objectionable part of the view' at The Fort, Bristol.

This Special Collections Spotlight article was contributed on 29 October 2013 by Charlotte Hoare, Library Graduate Trainee 2013-2014.