A direct, immediate, and obvious purpose

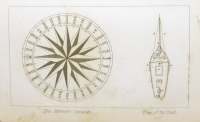

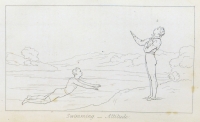

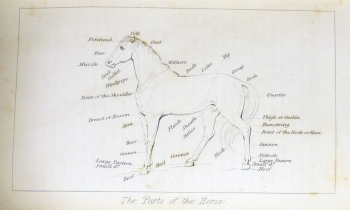

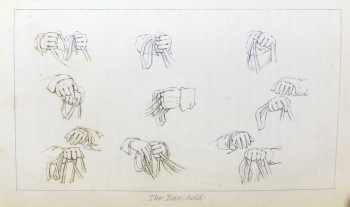

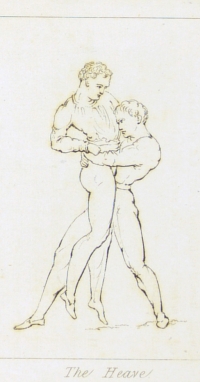

In the Gatty collection in the Lower Library is a copy of Donald Walker’s 1834 volume British Manly Exercises. Claiming to be the first book to describe the procedures of rowing and sailing as exercise, and the first of its kind to encompass the riding and driving of horses, the book is notable both for its delicate illustrations and for the charm of its prose.

Walker is plainly of the belief that nothing is worth doing unless it is done well, and he applies this principle to his writing as much as he expects people to apply it to their exercise. It is no great surprise that the book advertises a forthcoming treatise by the same author on the matter of literary composition: if writing a letter, for instance, is as common an occurence as going for a walk, there is no justification for either of them being done sloppily.

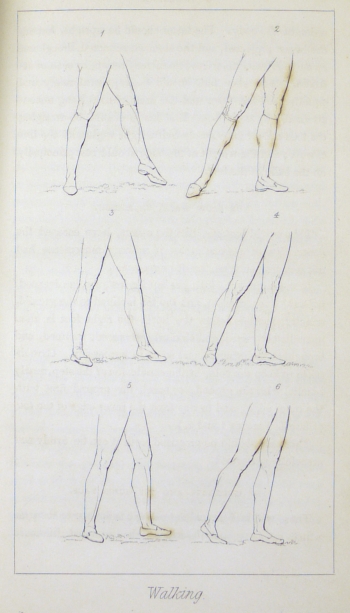

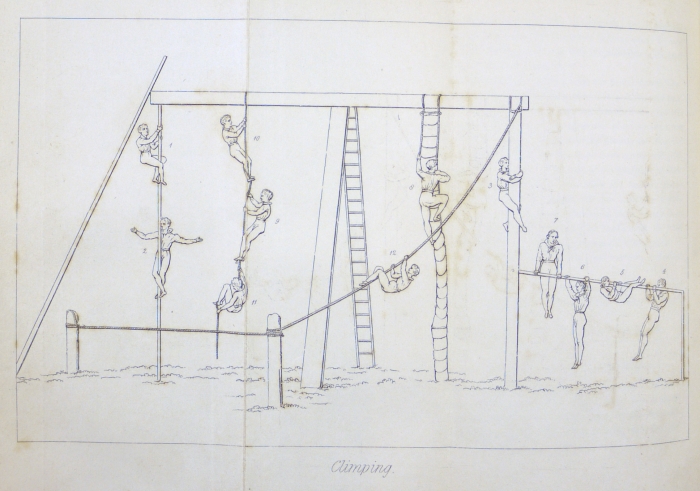

At points, the style seems as efficient as the workouts should be. Some activities are described with the dry precision of a (dry) dictionary: running 'is precisely intermediate to walking and leaping’, balancing is ‘the art of preserving the stability of the body upon a narrow or a moving surface’, and climbing is ‘the art of transporting the body in any direction, by the aid, in general, both of the hands and feet’. ‘Art’, however, is a key word in the latter two definitions: these things are not to be done artlessly, and are not being described as such either, as the author’s voice opens up to allow for tangents, observations, complaints, exaggerations, humour. True, Walker claims to value ‘useful exercises’ over ‘mere pastimes’, and to be divulging entirely sober and practical information:

All exhibitionary and quackish preparatory exercises , as they are termed, are here excluded; and nothing is introduced which has not a direct, immediate, and obvious purpose – no tick-tack, cross-touch, kissing the ground, goat’s jump, spectre’s march &c.

So much, a reader might think, for goat's jump. But one need not spend much time with the book to understand that at least as a stylist, and probably also as a sportsman, Walker is actually all for the flourish and the personal touch, as long as it is in service of an effective piece of work and provides no obstruction.

No exertion should be carried to excess, as that only exhausts and enfeebles the body. Therefore, whenever the gymnast feels tired, or falls behind his usual mark, he should resume his clothes, and walk home.

This warning against excess could be tidily recast as advice to writers, who probably shouldn't have had their clothes off in the first place.

And the information goes beyond mere technical direction. The reader is steered away from swimming in ponds, for example, as the sea is far preferable, while the skating chapter gives information on how to save the lives of those who have fallen through the ice. In the section on horses, meanwhile, Walker digresses on the role of the coachman, noting that improvements in roads have reduced the necessity for, and as such the number of, people skilled in this matter.

When in town, says a writer in the “Sporting Magazine”, I sometimes take a peep at the mails coming up to the Gloucester Coffee-house; and such a set of spoons are, I should hope, difficult to be found: they are all legs and wings; not one of them has his horses in hand; and they sit on their boxes – as if they were sitting on something else.

In the discussions of wrestling and boxing, the notions of the ‘British’ and the ‘manly’ are most enthusiastically explored, and Walker is as opinionated as he gets (which is to say, quite). He says of wrestling:

In England, its rules have been rather restricted. On the continent, they have admitted not only what has here been deemed more or less unfair, but what is positively so, as well as what is unseemly and disgusting.

And, in praise of the civilised nature of British (especially, predictably, southern English) boxing conventions, he refers by way of contrast to the ‘inhuman fights’ that take place in the United States, and to Ireland, where,

owing to ignorance of the generous rules of boxing and the spirit it inspires, a man who conceives himself aggrieved by another does not scruple to waylay him, and murder him with a bludgeon or a pitchfork, or to set fire to his cabin, and burn him or his family in their sleep.

Quite. Boxing (which he includes 'as the most valuable exercise in relation to the chest and lungs, and, in case of emergency, for self-defence, but by no means in approval of prize-fighting') is 'really useful to society as a refinement in natural combat’. Jonathan Gottschall has written more recently, in his 2015 book The Professor in the Cage: Why Men Fight and Why We Like to Watch, that bouts of refereed violence allow people to 'work out conflicts and thrash out hierarchies while minimizing carnage and social chaos'. Dated as Walker's title is, the concepts explored in its more philosophical portions remain relevant. 'Manly' isn't an unqualified reference to swaggering machismo: Walker is thinking about the ways in which properly physically exercising one’s manliness – or, let’s say, one’s humanity – can involve keeping elements of it at bay.

This Special Collections Spotlight article was contributed on 7 June 2016 by Adam Crothers, Library Assistant, who’s generally a bit hotter on literary style than on wrestling holds.