Chocolate

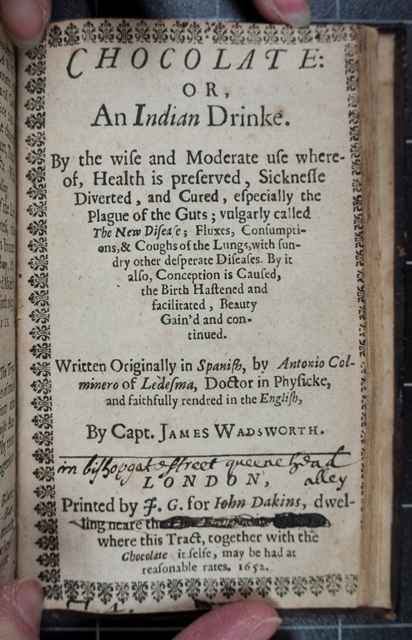

On a dark and chilly November afternoon, what could be more comforting than a steaming mug of hot chocolate? If Antonio Colminero of Ledesma, Doctor in Physicke is to be believed, it has many health benefits too. His book can be found in the Old Library, snappily titled: Chocolate, or, an Indian drinke: by the wise and moderate use whereof, health is preserved, sickenesse diverted, and cured, especially the plague of the guts; vulgarly called the new disease; fluxes, consumptions, & coughs of the lungs, with sundry other desperate deseases; by it also, conception is caused, the birth hastened and facilitated, beauty gain’d and continued. So to be fit and fertile, and look fabulous, this is the perfect drink! Our copy is an English translation, by Captain James Wadsworth, published in 1652. The enterprising printer sold not only the tract, but advertised that from his premises 'the chocolate it selfe, may be had at reasonable rates’.

On a dark and chilly November afternoon, what could be more comforting than a steaming mug of hot chocolate? If Antonio Colminero of Ledesma, Doctor in Physicke is to be believed, it has many health benefits too. His book can be found in the Old Library, snappily titled: Chocolate, or, an Indian drinke: by the wise and moderate use whereof, health is preserved, sickenesse diverted, and cured, especially the plague of the guts; vulgarly called the new disease; fluxes, consumptions, & coughs of the lungs, with sundry other desperate deseases; by it also, conception is caused, the birth hastened and facilitated, beauty gain’d and continued. So to be fit and fertile, and look fabulous, this is the perfect drink! Our copy is an English translation, by Captain James Wadsworth, published in 1652. The enterprising printer sold not only the tract, but advertised that from his premises 'the chocolate it selfe, may be had at reasonable rates’.

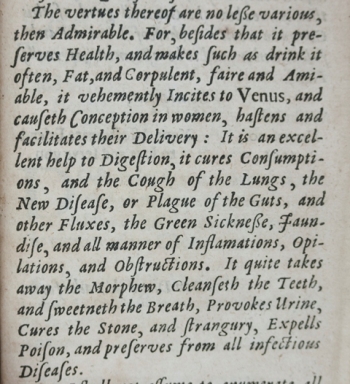

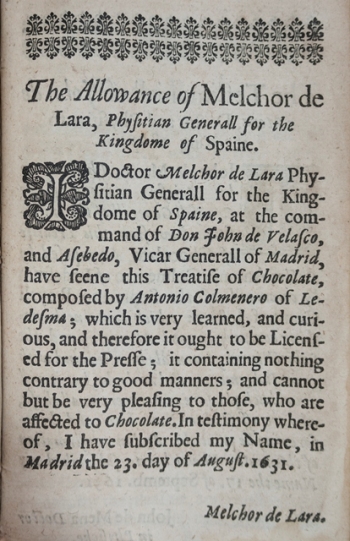

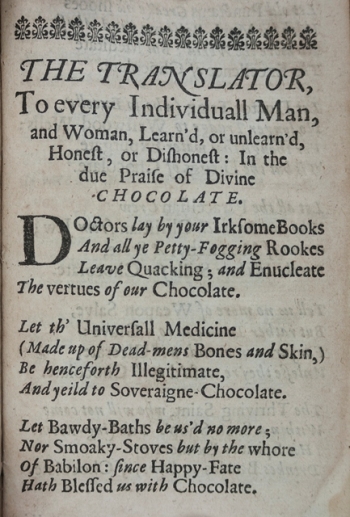

The work includes further descriptions of the health benefits to be gained from consuming chocolate, testimonials from prominent physicians affirming the truth of these claims, and several different recipes for making chocolate with information about the particular qualities of the ingredients used. The original text is supplemented with a poem in praise of chocolate by the translater, James Wadsworth.

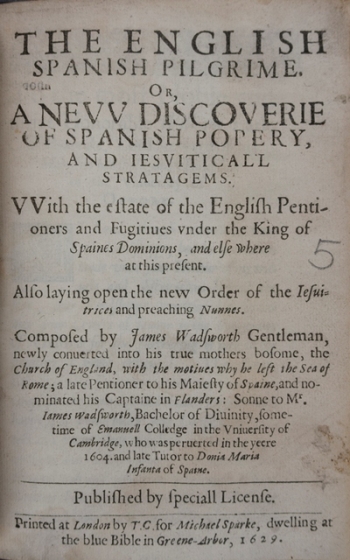

Wadsworth led a colourful life. He attended schools in Spain, where his family had converted to Roman Catholicism, before entering the English Jesuit College at St Omer in Artois. Whilst on a voyage with other students in 1622, he was first captured by the Dutch, then held to ransom by Moroccan pirates. In 1623 he acted as an interpreter for Prince Charles’ entourage in Madrid before being granted a commission in Philip IV’s Flanders army, though he was clearly more taken with using the title of captain than involvement in any battlefield action. In 1625, Wadsworth returned to England, renounced his Catholicism, and offered his services to the Privy Council as a spy. His career as a spy was singularly unsuccessful; his missions to Paris and Calais both resulted in ignominious imprisonment. Back in London, he wrote and published popular accounts of his adventures and experiences in Spain, highlighting the dangers of popery and his own prowess in dealing with pirates (the accuracy of some of his tales was much later contradicted when further contemporary sources came to light). He worked for two decades as a pursuivant, or messenger of the High Court, carrying out arrest warrants for a fee. 1640-41 saw him publishing again, first a translation of the treatise on chocolate, of which our copy is a later edition, and then a work on the highways and fairs of Europe aimed at travellers. He continued to collect pursuivant fees throughout the 1640s, appearing at several trials, and giving testimony against old schoolmates from the Jesuit College. Pursuivant work declined markedly after the civil war, leaving him impoverished. In 1656, a contemporary described him as a ‘renegade, proselyte, turncote of any religion’ now resident in Westminster and working as a ‘common Hackney to the basest catchpole Bayliffs’.

Wadsworth led a colourful life. He attended schools in Spain, where his family had converted to Roman Catholicism, before entering the English Jesuit College at St Omer in Artois. Whilst on a voyage with other students in 1622, he was first captured by the Dutch, then held to ransom by Moroccan pirates. In 1623 he acted as an interpreter for Prince Charles’ entourage in Madrid before being granted a commission in Philip IV’s Flanders army, though he was clearly more taken with using the title of captain than involvement in any battlefield action. In 1625, Wadsworth returned to England, renounced his Catholicism, and offered his services to the Privy Council as a spy. His career as a spy was singularly unsuccessful; his missions to Paris and Calais both resulted in ignominious imprisonment. Back in London, he wrote and published popular accounts of his adventures and experiences in Spain, highlighting the dangers of popery and his own prowess in dealing with pirates (the accuracy of some of his tales was much later contradicted when further contemporary sources came to light). He worked for two decades as a pursuivant, or messenger of the High Court, carrying out arrest warrants for a fee. 1640-41 saw him publishing again, first a translation of the treatise on chocolate, of which our copy is a later edition, and then a work on the highways and fairs of Europe aimed at travellers. He continued to collect pursuivant fees throughout the 1640s, appearing at several trials, and giving testimony against old schoolmates from the Jesuit College. Pursuivant work declined markedly after the civil war, leaving him impoverished. In 1656, a contemporary described him as a ‘renegade, proselyte, turncote of any religion’ now resident in Westminster and working as a ‘common Hackney to the basest catchpole Bayliffs’.

This Special Collections Spotlight article was contributed on 13 November 2015 by the Special Collections Librarian.